Surface temperatures over land are affected by the vertical turbulent exchange of heat and moisture from the surface to the atmosphere. While these processes are inherently complex, we show in our new article that by accounting for thermodynamic limits, the observed temperature patterns follow relatively simple and predictable rules.

Surface temperatures over land reflect the balance of heating and cooling. The surface is heated by solar radiation and the downward radiation emitted by the atmosphere — the atmospheric greenhouse effect — while it is cooled by emitting radiation, evaporating water, and transferring heat into the atmosphere (turbulent fluxes), which is accomplished by motion. While radiation processes are very well understood and commonly observed, the extent to which evaporation and motion cool the surface is less certain.

To quantify the latter two contributions, we applied a thermodynamic approach in which we assumed that the atmosphere works as hard as it can to cool the surface, generating maximum power for vertical motion. This approach views motion as the result of power generation from a heat-engine between surface and atmosphere (Figure 1), similar to how car engines generate power and motion from combustion. For the atmosphere, the fuel comes in form of the surface heating by radiation. But the consequences of generating motion also need to be taken into account. With more motion, you cool the surface more, and this makes the power generation process less efficient. This is like blowing over hot soup – the more you blow, the faster it cools. This cooling effect then results in a maximum that can power the atmosphere. This maximum can be calculated and used to quantify the cooling effects of evaporation and motion in land surface temperatures.

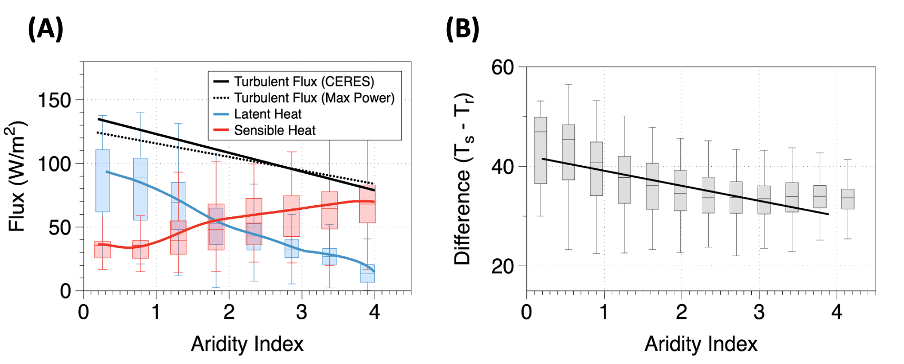

We used satellite-derived radiation datasets and implemented the maximum power approach at global scale to estimate heating and cooling rates across continents and seasons. With this, we predicted temperatures, evaporation, and heat fluxes that match observations remarkably well. We then applied this approach to understand why temperatures vary across continents the way they do, with deserts being warmer than rainforests. While it may seem that the lack of water and evaporation in deserts are the reason why they are warmer, what we found is that the lack of water is compensated for by more heat being transferred into the atmosphere (Figure 2a).

We then showed that dry regions are warmer primarily due to two factors. Firstly, they have less clouds, which increases the surface heating due to solar radiation. The second effect is less trivial: deserts are typically located in the subtropics, where the atmosphere transports heat horizontally through the so-called Hadley circulation. This heat is not added to the surface where it could drive the heat engine for motion, but to the atmosphere above. This makes the power generation process at the surface less efficient, resulting in less cooling and a warmer surface. Heat transport thus reduces the ability of atmosphere to exchange heat and moisture by weakening the heat engine. This weakening is similar to how a hot cup of coffee cools more rapidly on a cooler day compared to a hot day due to the increased temperature difference. In the Earth system, this difference is represented by the surface and atmospheric temperatures which decreases as we go towards drier conditions (Figure 2b). With these factors, we were able to explain the temperature variations from rainforests to deserts.

Our results show that thermodynamics imposes a relevant constraint on surface-atmosphere exchange and substantially simplifies the inherent complexities associated with it. It is not quite clear why this simple, but physical approach works so well. One way to understand it is that these processes are so complex that the ultimate limitation that they encounter is in the physics of power generation. Using this approach can further help us to increase our understanding about the response of land–atmosphere fluxes to changes in land cover, their interactions with vegetation, and their sensitivity to global warming.

References:

Ghausi, S. A., Tian, Y., Zehe, E., & Kleidon, A. (2023). Radiative controls by clouds and thermodynamics shape surface temperatures and turbulent fluxes over land. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120(29), e2220400120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2220400120