Rainfall events are expected to intensify everywhere because warmer air can hold more moisture. However, testing this relationship with observations across warmer regions and periods sometimes seem to contradict this expectation, showing negative or inconsistent trends. Our new study published in Nature Communications and led by Sarosh shows that it is mainly the cooling effect of clouds associated with rainfall that causes these discrepancies. By accounting for this effect, we resolve the apparent mismatch between observations and theory, providing evidence of increases in extreme rainfall with warmer temperatures. More information in this blogpost and in the paper.

Discrepancy in observation-based estimates and expectations

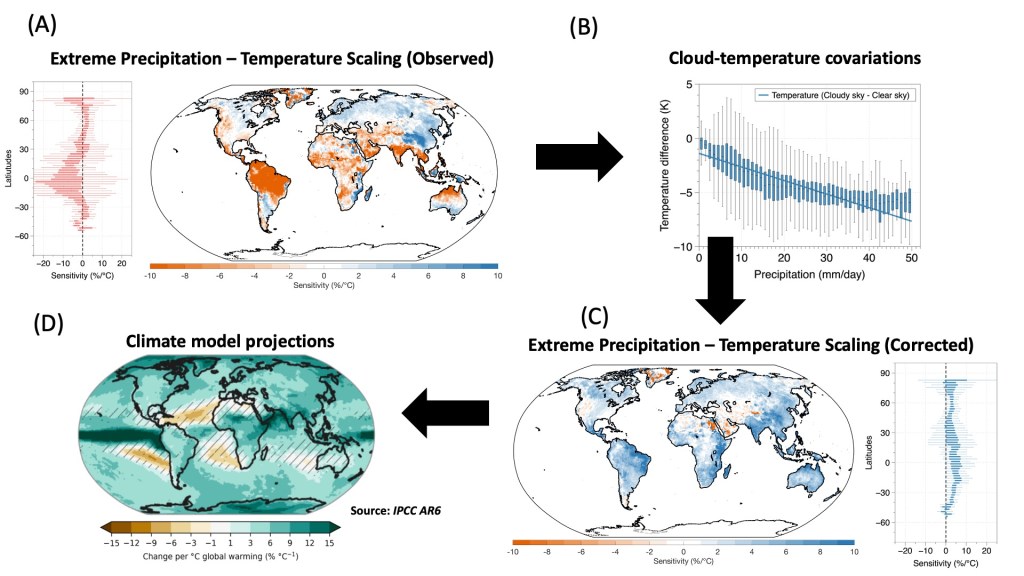

Extreme rainfall is usually defined as the heaviest five percent of rain events in a specific area. As the global temperature rises, these events are expected to become even heavier. This intensification is linked to the ability of air to hold more moisture (or more technically, the increase in the saturation vapor pressure with temperatures – see also this blogpost). To determine this intensification, many studies use observed extreme precipitation events and test how these change with observed local temperatures. These so-called scaling rates differ from what is expected from theory, showing a decline above temperatures of around 23° – 25°C. This is referred to as “breakdown” in scaling (Hardwick et al., 2010; Bao et al., 2017; Ghausi et al., 2022). As a result, the extreme precipitation – temperature (EP-T) sensitivities derived from observations across the humid tropics show mostly negative values (Figure 1 A) in contrast to positive changes projected by climate models (Figure 1 D). This makes it difficult to interpret the precipitation response to global warming. It also raises the question of whether a high-temperature threshold limits the increase in the intensity of precipitation events with rising temperatures.

Cloud-induced covariation between rainfall and temperature

In our paper, we identify the cooling caused by clouds during rainfall as the major factor that distorts the observed precipitation-temperature scaling relationships, resulting in breakdowns. Clouds associated with rainfall events play a critical role in cooling the surface by reflecting sunlight and reducing the local radiative heating at the surface. For instance, see our paper Ghausi et al. (2023), where we showed how clouds modulate temperatures across dry and humid regions. This cooling by clouds introduces a covariation between rainfall and temperature beyond temperature’s effect on atmospheric moisture-holding capacity. This effect is particularly significant in the tropical regions where solar insolation and temperatures are high. As a result, regions and periods of more intense precipitation cool more (Figure 1 B) and this affects their position in the scaling curve. The strongest rainfall events are shifted to lower temperature bins and the warmest bins are populated only by events with a weaker cooling effect, causing the bin-shifting effect. As a result, the apparent sensitivity of precipitation to temperature gets biased by the redistribution of extreme events into cooler bins.This obscures the apparent relationship between extreme rainfall and temperature, leading to underestimations of the true sensitivity of extreme precipitation to warming.

Removing the cloud effects from temperatures

To remove the effect of clouds on surface temperatures, we used a surface energy balance approach where the turbulent heat fluxes are explicitly constrained by the thermodynamic limit of maximum power. We have already shown in our previous papers that this approach works very well in reproducing surface temperatures and turbulent fluxes over land (Kleidon and Renner, 2018; Conte et al., 2019; Ghausi et al., 2023). By using this additional constraint together with the “all-sky” and “clear-sky” radiative fluxes from NASA-CERES satellite data as forcings, we estimate changes in surface temperatures associated with cloud radiative effects during rainfall events. Subsequently, we use them to evaluate the impact of clouds on rainfall-temperature scaling.

Extreme rainfall sensitivities after adjusting for cloud effects

After correcting the local temperatures for cloud cooling effects, we find positive EP-T sensitivities across continents, consistent with theoretical arguments and climate model projections (Figure 1 D). Median EP-T sensitivities across observations shift from −4.9%/°C to 6.1%/°C in the tropics and −0.5%/°C to 2.8%/°C in mid-latitudes. Regional variability in estimated sensitivities is reduced by more than 40% in tropics and about 30% in mid and high latitudes. Our findings imply that the projected intensification of extreme rainfall with temperature is consistent with observations across continents, after the confounding radiative effect of clouds is accounted for. Our methodology to remove the effects of cloud cooling is also likely to allow us to derive climate sensitivities from observations beyond precipitation events.

Lastly, this study also nicely illustrates that one needs to take a look at the whole system to identify seemingly simple relationships, because rainfall and temperature are connected with each other in multiple ways.

Reference to publication:

Ghausi, S.A., Zehe, E., Ghosh, S., Tian, Y., Kleidon, A. (2024). Thermodynamically inconsistent extreme precipitation sensitivities across continents driven by cloud-radiative effects. Nat Commun 15, 10669. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55143-8