It only takes a little basic physics to describe the essence of the hydrological cycle. This allows us to reproduce climatological variations and the changes with global climate change very well. It is described in a recently published article (english translation on arXiv) and is explained in two YouTube videos on basics and droughts and on heavy rainfall (in German, but you can use subtitles).

The hydrological cycle in action – the Sun provides the energy for evaporation at the Earth surface, water vapor provides the energy for precipitation dynamics in the atmosphere.

This new article on „Droughts in Germany“ was recently published in Physik in unserer Zeit (translation available on arXiv). The article deals first with the thermodynamics of the hydrological cycle, in particular which processes perform work and how they can be described by heat engines and thermodynamic limits in the context of the Earth as a whole. It then performs an analysis of droughts in Germany and how these have increased over the last few decades due to global warming. Observation-based data sets from the German Weather Service are used and combined with the thermodynamic approach. This analysis shows how much global climate change and drier conditions have already affected Germany. These aspects are also described in this video on the YouTube channel Urknall, Weltall und das Leben and on Videowissen.

Below I will give a brief summary. I am planning a separate blog post on climate change in Germany in the near future.

The hydrological cycle operates far from equilibrium

From a physical point of view, the hydrological cycle is a system that operates far from what is known as thermodynamic equilibrium. Equilibrium is saturated air. This is a boring state because practically nothing happens in it. In this state, the rate of evaporation, i.e. the phase transition from liquid water to the gaseous state, balances with the rate of condensation, the reverse phase transition from gaseous to liquid. This balance takes place locally and continuously. A good image for such a state is a foggy day in November.

The hydrological cycle of the Earth system represents a state far from this equilibrium. Saturation does occur, but only relatively rarely and only locally. By and large, the atmosphere is mostly unsaturated, and evaporation and precipitation are separated from each other in space and time. This represents this disequilibrium.

The hydrological cycle oscillates between two phases

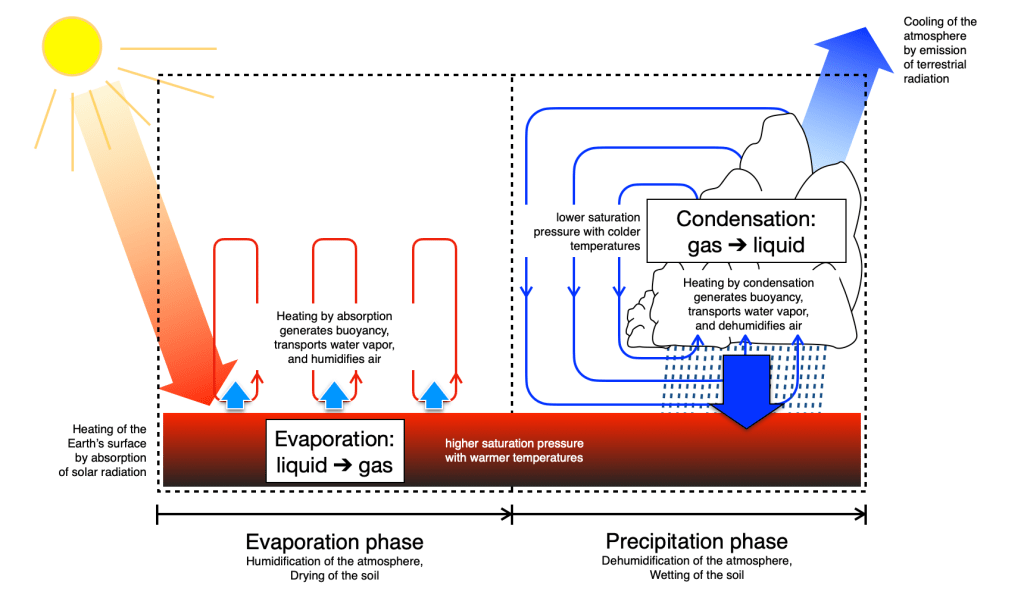

We can therefore divide the dynamics of the hydrological cycle into two phases (see Figure below):

The evaporation phase: In this phase, water vapor is added to the atmosphere and the disequilibrium of unsaturated air is reduced. Evaporation takes place mainly at the surface and it requires a lot of energy. This energy comes mainly from absorbed solar radiation and is limited by the energy balance of the Earth’s surface and by thermodynamics – the latter twice: on the one hand, saturated air can maximally be added to the atmosphere, and on the other hand, work is needed to mix air vertically and thus bring the evaporated water into the atmosphere. The combination of both describes the so-called potential evaporation, i.e. evaporation when sufficient water at the surface is available (see also Kleidon et al. 2014, Conte et al. 2019, Kleidon 2021).

The precipitation phase: When air rises and becomes cooler, water vapor can condense and form clouds. The energy that was used by evaporation is released again. The air in the cloud is heated, generates buoyancy, it continues to rise, and draws more moist air with it. Work is done by accelerating and dehumidifying air. Precipitation, air motion and disequilibrium in the form of unsaturated air are created. This dynamic can be clearly seen in thunderclouds or in the form of the tropical circulation, i.e., the Hadley cell.

Schematic division of the hydrological cycle into an evaporation phase and a precipitation phase. From Kleidon (2024).

We can now imagine the hydrological cycle as oscillating back and forth between these two phases. The evaporation phase usually lasts longer because the energy for evaporation dynamics is limited by the input of solar radiation. The precipitation phase is much shorter because it draws energy from the condensation of water vapor stored in the air. This released energy heats the air in the cloud, creates uplift, draws in more moist air, thereby creating more uplift and therefore accelerating itself.

Global warming increases the amplitude of this pendulum dynamics

With global climate change, the downward emission of radiation by the atmosphere to the surface increases. This means that more energy is available, and the surface becomes warmer. Potential evaporation therefore increases with climate change – there is more energy, and at warmer temperatures this promotes the partitioning at the surface in favor of evaporation.

The atmosphere also becomes warmer, at least its lower part, which holds the water vapor. And warmer air can hold more water vapor. The water vapor content in saturated air is then mathematically described by the so-called Clausius-Clapeyron equation. It leads to the saturation vapor pressure curve, i.e. a quasi-exponential increase in water vapor with air temperature. This is the equation that states that warmer air can hold more water vapor – about 7% per degree of warming. Even if the atmosphere is not completely saturated, this sets the upper limit for the oscillation of the hydrological cycle between evaporation and precipitation. The lower limit is set by the maximum work derived from condensational heating which dehumidifies the atmosphere.

Global warming therefore has serious consequences for the hydrological cycle. Evaporation increases, as already described. Because the atmosphere can hold more water vapor, the amplitude of the oscillation between the phases is increased. Precipitation thus becomes more intense, more powerful and shorter. And because the ability of the atmosphere to hold water vapor increases more per degree of warming than evaporation, the evaporation period generally becomes longer. Dry periods therefore increase, precipitation events tend to decrease, but they become more intense. And shorter periods of precipitation should then also lead to shorter-lived clouds. In other words, more solar radiation at the surface, which then further increases warming and evaporation.

More about this, especially how this can be described with equations and thus how drought can be determined in Germany, can be found in the article. It is explained in more detail in the YouTube videos (see below).

Videos

The first video describes the basics of disequilibrium of the hydrologic cycle, the limits to evaporation, and shows the analysis of greater dryness in Germany over the last few decades.

The second video focuses on the power generated by condensation, its implications for climate in form of the Hadley cell, and describes hypotheses regarding global climate change and the hydrological cycle, such as the „wet-gets-wetter“ hypothesis.

References

Kleidon, A. and Renner, M. (2013) Thermodynamic limits of hydrologic cycling within the Earth system: concepts, estimates and implications, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 17, 2873–2892, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-17-2873-2013.

Kleidon, A., Renner, M., and Porada, P. (2014) Estimates of the climatological land surface energy and water balance derived from maximum convective power, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 18, 2201–2218, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-18-2201-2014.

Kleidon A. (2016) Hydrologic cycling. In: Thermodynamic Foundations of the Earth System. Cambridge University Press; 2016: 188-218.

Conte, L., Renner, M., Brando, P., Oliveira dos Santos, C., Silvério, D., Kolle, O., et al. (2019) Effects of tropical deforestation on surface energy balance partitioning in southeastern Amazonia estimated from maximum convective power. Geophysical Research Letters, 46, 4396–4403. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018GL081625

Kleidon, A. (2021) What limits photosynthesis? Identifying the thermodynamic constraints of the terrestrial biosphere within the Earth system, Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) – Bioenergetics, 1862: 148303, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbabio.2020.148303.

Kleidon, A. (2024) Dürren in Deutschland. Phys. Unserer Zeit, 55: 190-197. https://doi.org/10.1002/piuz.202401697