About 15 years ago I published a paper on “Life, hierarchy, and the thermodynamic machinery of planet Earth”. This paper was quite influential for me as it clarified many things about how the second law of thermodynamics applies to the Earth system. It led to quite a few applications of thermodynamic limits in climate science and renewable energy that worked really well and that I found insightful because it allows us to do climate science in a simple yet physically-based way. The follow-up paper just published provides a summary of this approach and explores potential, more concrete applications of how the biosphere optimizes its form and functioning, and on life on Earth and beyond in general.

Entropy often has an almost mystic flair, and so does the second law of thermodynamics. Clearly, the second law of thermodynamics must apply to the Earth system as well, but how, and what can we learn from it? Considerations of the second law in Earth system science are strangely rare. In the original paper, I described my key insight: that entropy and the second law matter mostly because they limit how much work – such as accelerating air, lifting water, or producing carbohydrates – can be derived from sunlight. This work then drives the dissipative systems of the Earth that convert this work back into heat.

This perspective – that the interesting processes perform or use work, as opposed to boring processes such as diffusion that do not involve work – is also strangely absent in Earth system science. For myself, this paper was a big step forward, after a couple of years being involved in evaluating the hypothesis that systems maximize entropy production (the Maximum Entropy Production (MEP) hypothesis). The difference to work and power is simple – while essentially all processes produce entropy, some first perform work and do things with this work before entropy is being produced.

The interesting Earth system processes perform work

There are only a few mechanisms that can generate work from sunlight. The simplest is a heat engine that is driven by differences where heating and cooling takes place. The surface is heated by absorption, the atmosphere cools by emission to space, and this differential heating sets the conditions to create motion in form of buoyancy and updrafts. This mechanism is what drives climate system processes. Likewise, the difference in heating and cooling between the tropics and the poles sets the conditions to generate the work needed to sustain the large-scale motion of the atmosphere.

Once work is performed, this useful energy in form of motion is then converted further, e.g., generating ocean waves, or it is dissipated into heat by friction. Adding this heat at a certain temperature adds entropy to the system. Or you can say that this dissipative process, such as friction, produces entropy. In other words, when work is derived from sunlight, this delays entropy being produced.

There are two other mechanisms that generate work from sunlight that are not heat engines: photosynthesis and photovoltaics. They use solar radiation before it turns into heat and perform the work of separating electric charges – with photosynthesis converting this electric energy further into chemical form as carbohydrates and oxygen. And this links directly to life and human activity, and the potential effects these can have on planetary functioning.

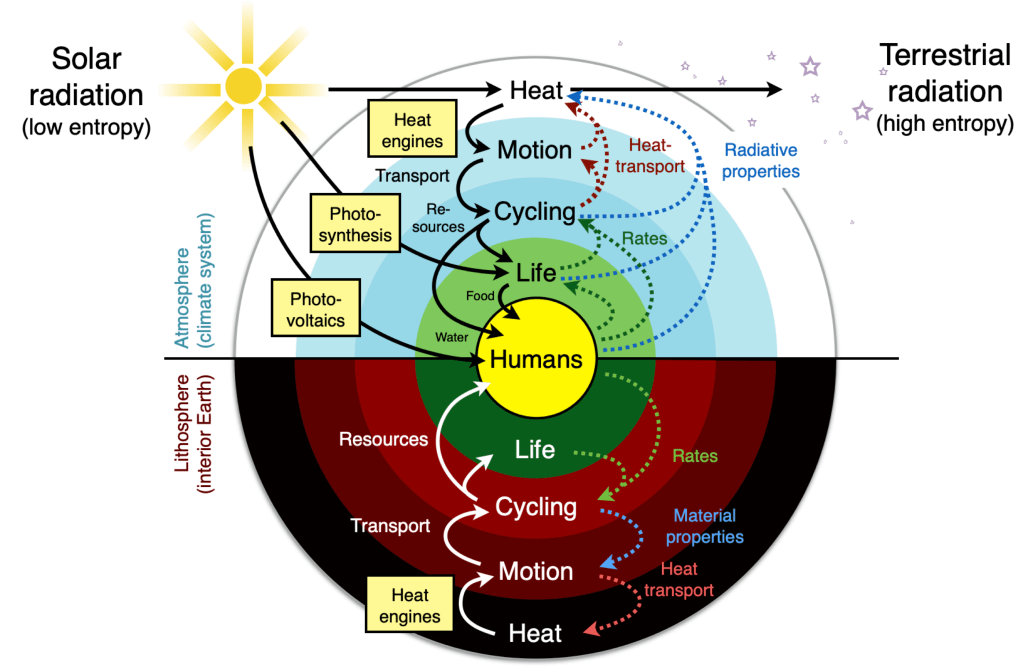

Figure 1: Energy transformations of the Earth system represent a hierarchy that follow the second law. Entropy plays a critical role in these transformations as it limits the amount of work that can be derived from sunlight. From Kleidon (2023), updated after Kleidon (2010, 2016).

This view of work on Earth being performed from sunlight and how life affects it is summarized by what I call the „onion“ (see Figure 1). It shows the planetary forcing, in terms of solar radiation being an energy source of low entropy and the emission of high-entropy radiation to space, the three mechanisms that derive work from sunlight, and the different forms of energy that are involved in the dynamics of Earth system processes – from heat to the kinetic energy in motion, various forms such as chemical and potential energies associated with cycling, life and human systems. It reflects a clear causality that is ultimately related to the second law – differences in radiative fluxes cause differences in heating and cooling, these differences are used to perform work to generate motion.

But there are also effects that result from this work that alter the drivers. Motion transports and redistributes heat, and this affects radiative fluxes between Earth and the surrounding space, and thus the entropy exchange. These interactions are highly relevant, because they affect the limit to how much motion can be generated, although their magnitude is also constrained by the overall thermodynamic setting of the planet. In effect, this leads to a maximum power limit, which can be used to determine the magnitude of heat transport and thereby provide an additional constraint to the energy balances within the Earth system.

Thermodynamics constrains life indirectly by transport

I was recently asked to give an update on my 2010 paper for a special issue on occasion of the 20th anniversary of the journal Physics of Life Reviews. In the new paper I reflect on how successful this thermodynamic Earth system approach has been to make simple yet profound and physically-based predictions, primarily of the climate system and its response to change. These applications were focused on applications to energy balances and the hydrological cycle, and less so on the role of life. In fact, the results seemed to suggest that thermodynamic constraints alone are sufficient – after all, we showed, e.g., in Conte et al. (2019) that rainforest evaporation can be predicted from thermodynamics essentially without any knowledge of the rainforest. This seemed to dwarf the role of life in Earth system functioning.

So this occasion of revisiting the “onion” presented a nice opportunity to look again at the role of life on Earth. One important aspect that I have learned since 2010 is that I increasingly appreciate the critical role of motion in the Earth system. From the perspective of cycling mass, motion maintains the turbulent exchange of mass between the surface and the atmosphere. And this exchange is critical to maintain phase transitions (such as evaporation and precipitation, that is, the hydrological cycle) and chemical reactions (such as photosynthesis, that is, the activity of the biosphere). Thermodynamics and its limits then act indirectly on such processes in that these constrain how much motion and exchange takes place on Earth. This interpretation is then consistent with the notion of equilibrium evaporation in hydrology, and it can explain the low efficiency of photosynthesis in natural systems (Kleidon 2021, 2023).

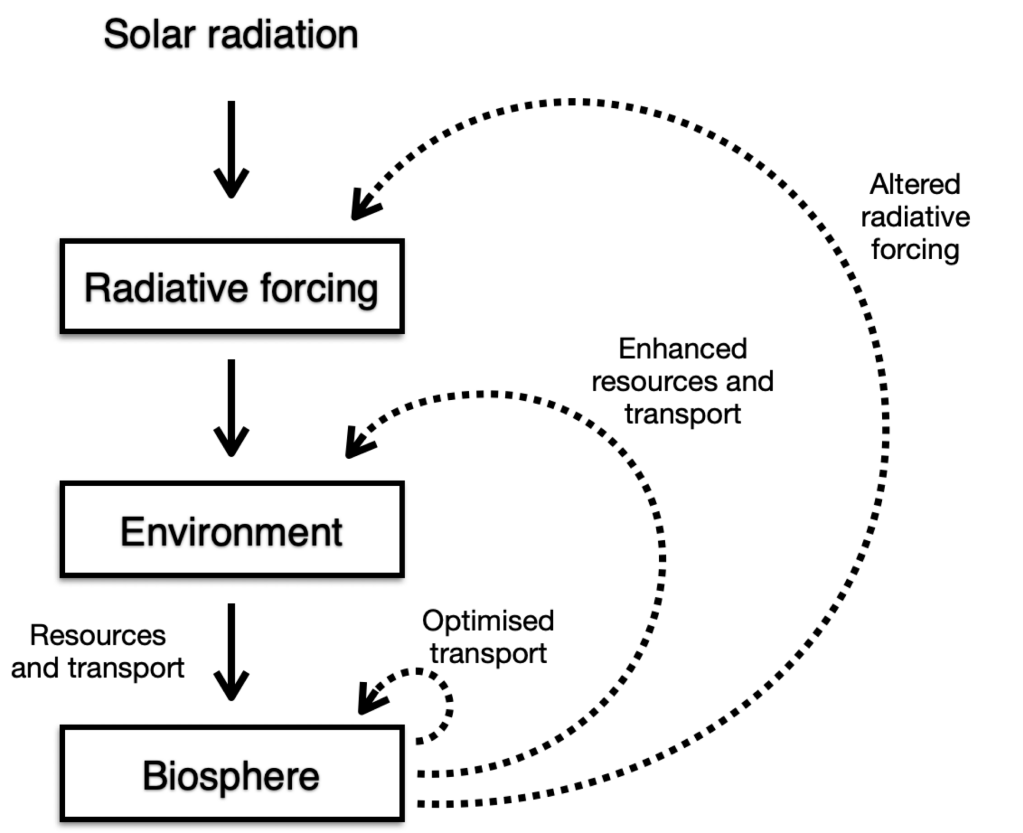

Figure 2: Life optimises transport limitations by different means: by optimising transport within their organisms (e.g., by fractal vascular networks and self-thinning laws), by enhancing resources and transport within the environment (e.g., by deeply reaching rooting systems and nutrient transport by animals), and by altering the radiative forcing of the environment (e.g., by altering concentrations of carbon dioxide and oxygen).

When looking at optimality and maximizing the power of the biosphere, this then shifts the focus on mechanisms that life has to minimize transport restrictions. Less friction means faster transport and cycling, affecting resource availability. This affects the environmental conditions for the biosphere to be productive and generate power from sunlight (Figure 2).

There are various means to alter transport, linking to other, already established concepts. For instance, the beautiful work on fractal networks by Enquist, West and coworkers (e.g., West et al. 1997, Enquist et al. 1998) is based on the assumption of minimizing frictional dissipation – that is, minimizing transport restrictions within organisms. It sheds light on the potential role of animals in the biosphere, as means to accelerate the release of nutrients from organic material because their digestive systems provide ideal environments for decomposition (as stated, e.g., by the optimal grazing hypothesis, McNaughton 1979) and the redistribution of resources against physical gradients because animals can perform work and move (e.g, Buendia et al. 2018, Dougherty et al. 2016). These effects are likely to make the biosphere more productive. Then, more carbon dioxide is taken up from the atmosphere, altering its chemical composition, particularly regarding carbon dioxide and oxygen. This ultimately changes the radiative conditions of the planet that set the radiative conditions for the transport constraints in the first place. This, in turn, would seem to relate closely to the Gaia hypothesis of Lovelock that the Earth with life may regulate itself in a state that allows for a most active biosphere (Kleidon 2023).

The way ahead

To me, this picture of life on the planet makes a lot of sense. It is quite a concrete picture of how the second law of thermodynamics shapes the dynamics, how it manifests itself in the structure of the biosphere, and how this can result in better predictive outcomes.

This picture is certainly not finished. Ideally, it would yield an approach that is as quantitative and successful as our applications of maximum power to climate science. There seems to be plenty of work left to do for a more detailed, thermodynamically-informed description of the biosphere. This would, for instance, include more explicit considerations of fractals, the inclusion of food webs in the dynamics, and smarter, adaptive evolutionary models of the biosphere that are able to optimise and yield such fractal patterns.

Well, let’s see where the next 15 years will take us!

Related popular science material (in German)

Was begrenzt das Leben? Article in Physik in unserer Zeit.