What can we learn from entropy about life on Earth? In this series of videos, I aim to provide the thermodynamic and Earth system background to answer this question. The videos are based on two lectures that I gave in Padova in July 2025. I split the lectures up into an introduction, six questions, and a summary, each in a separate video. This blogpost provides a brief description of the different videos, references for further reading, and the links.

Introduction

Video also available here: https://doi.org/10.5446/71169

Part I: What is entropy?

Entropy – we typically associate this term with the concept introduced by Clausius in the mid-19th century, at a time when steam engines were being developed and rapid industrialization took place. However, the concept continued to evolve. Boltzmann’s kinetic theory of gases gave entropy a statistical basis, which Planck then used to derive the laws of radiation. Entropy thus evolved from something empirical to a core concept of quantum physics and statistical mechanics. Energy is quantized and distributed across photons, electrons, and vibrational states of molecules of different energy. Consequently, there are at least three forms of entropy associated with the distribution of quanta of energy across photons, electrons, and molecules. The most probable distribution, i.e., maximum entropy, is needed to translate the properties from the molecular level to classical physics.

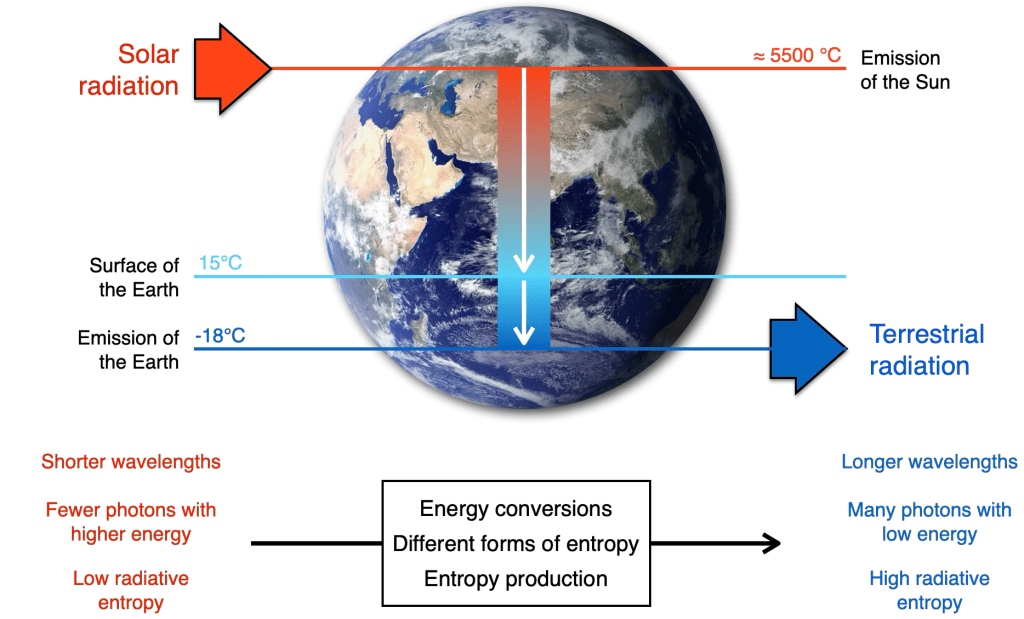

The three forms of entropy are needed to understand energy transformations on Earth, where entropy changes its forms as energy is converted (Kleidon 2010, 2016, 2023). The sun radiates energy into space at very high temperatures. When this radiation reaches the Earth, it has therefore very low entropy – the energy is distributed over comparatively few energetic photons with short wavelengths. The processes of the Earth system convert this energy, as well as the form of entropy, during absorption, emission, heating and cooling, buoyancy, friction, phase transitions, geochemical reactions, and all other processes of the Earth system. When the energy is finally radiated back into space, it is distributed over many more photons, each with lower energy. Thus, entropy increases substantially during these transformations, following the second law of thermodynamics. But, in a way, that is not really surprising, but what you would expect.

Video also available here: https://doi.org/10.5446/71170

Part II: Why is entropy relevant?

Entropy becomes relevant when we take a closer look at how it is actually increased. There are basically two different types of processes: (1) those that directly increase entropy and reduce differences, such as radiative transfer (i.e., sequences of absorption and emission of radiation), diffusion, or mixing, and (2) those that first perform work, generate usable energy, and only generate entropy when this usable energy is consumed, i.e., dissipated and converted back into heat again at a certain temperature. In the latter case, energy takes a detour, causing dynamics and shaping the interesting aspects of the Earth system.

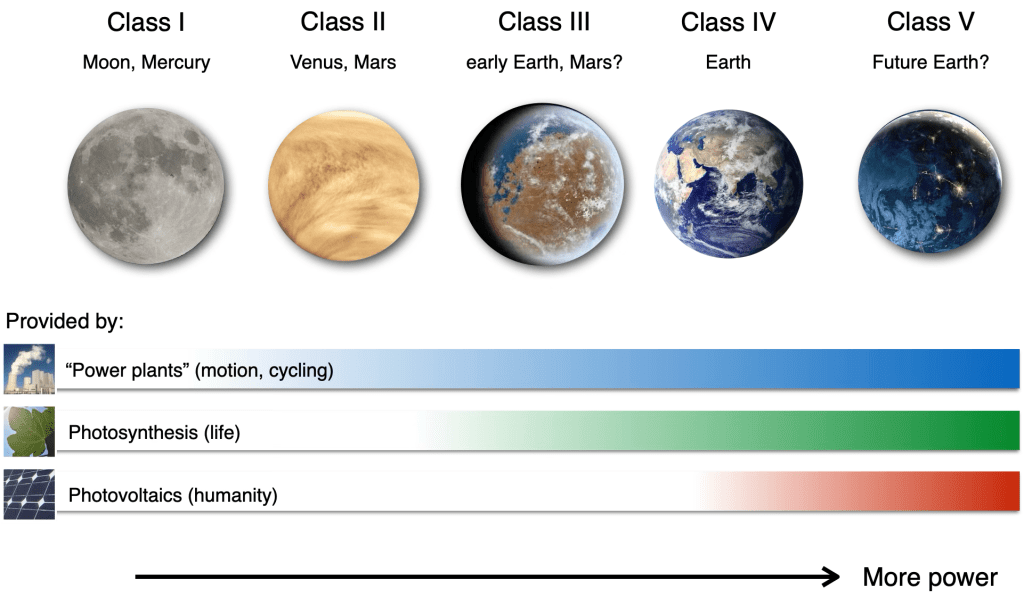

For the latter type, entropy sets the limit on how much usable energy can be generated — just like in a power plant, which generates usable energy in the form of electricity from the heat of combustion (i.e., energy with low entropy). On Earth, there are ultimately three processes that extract work from sunlight: (1) heat engines of the climate system, which generate motion from heat that is ultimately dissipated again through friction; (2) photosynthesis, which performs the work of charge separation to form chemical energy and keeps life going; and (3) photovoltaics, which directly generates electricity that is consumed by human societies.

Entropy is thus relevant because it sets the speed limits to the dynamics of the Earth system.

Video also available here: https://doi.org/10.5446/71171

Part III: What is life?

How does life fit into this picture? Life needs food, i.e., usable energy in chemical form, to maintain metabolic activity. The sum of all life, i.e., the biosphere, forms a dissipative system. It is fueled by the producers, which generate usable chemical energy from sunlight through photosynthesis, and consumers, which take up this energy as food and convert it back into heat through their metabolisms. And the heat released due to metabolic activity at the ambient temperature of the energy – that increases the entropy.

Thermodynamics therefore allows us to clearly measure the activity of the biosphere through the rate by which it generates useable energy and its dissipation. It is a measure that can be used to quantify the dynamics of all other Earth system processes as well, so it provides a general basis to evaluate how powerful different processes of the Earth system are, and how beneficial an environment is for life – a better environment allows for more dissipative activity of the biosphere.

Video also available here: https://doi.org/10.5446/71172

Part IV: What limits life?

What limits the activity of the biosphere? At first glance, one might think of applying something like the Carnot efficiency to photosynthesis – but this only shows that observed rates of photosynthesis are significantly below the maximum that thermodynamics would allow, so it requires a somewhat broader look at what limits life.

A closer look reveals that the actual limitation lies in the exchange of matter with the environment (Kleidon 2021). Plants on land must absorb carbon dioxide (CO2) from the air for photosynthesis, evaporating a lot of water while doing so. The ratio between CO2 uptake and water loss is relatively fixed (known as the water use efficiency), varying only slightly between different ecosystems and climates. Evaporation into the atmosphere, in turn, is clearly limited by thermodynamics – by the rate at which water vapor is released into the atmosphere. This shows that the activity of the biosphere (at least on land) is indeed limited by thermodynamics, albeit indirectly, in that the gas exchange between vegetated canopies and the atmosphere near the ground is limited. This explains its very low efficiency. Because of this limitation, the activity of the biosphere is ultimately predictable by the physical conditions because they describe this constraint.

However, the biosphere is not helplessly at the mercy of these thermodynamic limits. Effects of the biosphere can change the environment in such a way that these limits are being pushed to allow for higher levels of dissipative activity. One example is the effect of roots on vegetation. The depth of the rooting zone determines how much soil water can be reached by vegetation for evaporation. This means that a vegetated area can evaporate more than a bare surface. With more evaporation, vegetation can do more gas exchange and can therefore be more productive (see e.g., Kleidon, 2023).

This is one effect that shifts the limits of water availability in a positive direction—the biosphere performs and dissipates more as a result. There are other effects as well, e.g, the decomposition of organic material and nutrient transport by the consumers (i.e., animals), as well as the effects on atmospheric conditions. With these, the biosphere exhibits the means to change the environment, to improve it to such conditions that allow for higher levels of dissipative activity of the whole biosphere (Kleidon, 2024).

Video also available here: https://doi.org/10.5446/71173

Part V: How did life shape Earth’s history?

Whether the biosphere did improve the planetary conditions, that is something we can check by looking at how the Earth has evolved in its past. Over the course of 4.5 billion years, life has dramatically changed the composition of the atmosphere. Reconstructions (e.g., Catling & Zahle, 2020) show that the general trend is that the concentration of greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide and methane, has been significantly reduced, and that the oxygen content has increased due to the accumulation of biomass, the deposition of organic material that form fossil fuels, and the acceleration of weathering, which resulted in enhanced deposition of limestone. From a thermodynamic point of view, this means that life has created a huge planetary disequilibrium in the form of reduced carbon and atmospheric oxygen, and this has massively changed the radiative conditions for energy conversions on Earth.

This enormous change in turn has an effect on energy conversions. Now, of course, we can ask ourselves whether these feedbacks have ultimately increased or even maximized the dissipative activity of the biosphere on a long time scale (Kleidon, 2023), similar to how the rooting depth of vegetation does it or the generation of motion within the atmosphere does. The resulting function of the Earth system would then be quite similar to the behavior postulated by James Lovelock’s Gaia hypothesis: that the biosphere optimizes its environmental conditions to perform at its best.

This long-term improvement of planetary conditions, even a potential maximization, is consistent with the observed changes of the Earth’s past, but would need some further confirmations. What is nevertheless clear is that life has created a massive state of thermodynamic disequilibrium, in form of reduced carbon compounds and atmospheric oxygen.

Video also available here: https://doi.org/10.5446/71176

Part VI: How do humans affect the Earth?

This massive disequilibrium that life has generated is something that currently fuels human societies. This, in turn, enhances the atmospheric greenhouse effect, causes global warming, and undoes the work of the biosphere (Kleidon, 2023).

The solution is obvious. Stop burning fossil fuels and generate energy yourself using photovoltaics to yield the energy needs of human societies and maintain, and even potentially enhance, their disequilibrium states. This is where the third process comes into play, which can perform work from sunlight: photovoltaics. It is already much more efficient than photosynthesis, allowing the Earth to generate more power from incident solar radiation. Human technology would then be a manifestation of the continuation of processes that can increase the work done by planetary systems (Frank et al., 2017).

Video also available here: https://doi.org/10.5446/71174

Summary

Video also available here: https://doi.org/10.5446/71175