Wind turbines generate electricity by removing kinetic energy from the winds – after all, that is what they are designed to do. The more wind turbines are deployed within a region, the more the wind speeds must be reduced, thereby impacting the wind resource potential of the region. In our new paper we tested our KEBA approach with much more complex numerical weather simulations and found that accounting for the removal of kinetic energy captures the dominant effect, but one also needs to distinguish between daytime and nighttime conditions. This removal effect lowers the resource potential of Kansas by more than 60%, but still yields substantial amounts of electricity – more than Germany currently consumes. More infos in the blogpost and in the paper.

Why simple, yet physics-based estimates of wind resource potentials are needed

Many approaches use observed wind speeds to estimate how much wind energy can potentially be generated. What may sound appropriate and realistic leads to a problem when wind energy is used more and more intensely at larger and larger scales. This is because each wind turbine removes some of the energy of the wind. The more wind turbines there are within a region, the more the wind resource is being depleted. With a depleted wind resource, the wind turbines within the region become on average less efficient because the wind fields are weakened. This follows directly from simple physics: The atmosphere works as hard as it can to generate motion, and using wind energy competes against the natural dissipation of motion by friction near the surface (see Figure). The more of the kinetic energy of the winds is being used by wind turbines, the less goes into friction – and this is associated with lower wind speeds. This effect needs to be accounted for when one considers larger-scale deployment of wind energy, as is expected in energy scenarios for the future.

This effect of larger-scale wind energy use has already been evaluated for some time using numerical simulation models (including our own work, e.g. Miller et al. 2011). This may also sound reasonable, after all we deal with a highly complex problem. Yet, for energy policy and scenarios, such highly detailed simulations are far too complex. So how can we approach this effect of wind turbines in a fairly simple and pragmatic way that is nevertheless based on processes and physics, and by looking at the whole system? I think such simple approaches are essential, for making better estimates for policy-related work, but also to make science more transparent and to communicate insights.

In my group, we developed two approaches that are based on kinetic energy. Basically, we „follow the energy“, from the limited ability of the atmosphere to generate motion (using our thermodynamic approach, Kleidon 2021) to its depletion by friction near the surface or its utilization by wind turbines. One of the approaches we refer to as VKE (Miller et al. 2011, Miller et al. 2015), for vertical kinetic energy flux approach. This approach applies to large-scale use of wind energy and neglects differences in horizontal in- and outflows. At the regional scale, we developed the Kinetic Energy Budget of the Atmosphere (KEBA) approach (Kleidon and Miller 2020) that accounts for differences in the horizontal flow and applies to regional scales. These approaches have worked really well so far in that they are able to reproduce the behavior of much more complex numerical models. They have been applied to e.g., evaluating the offshore wind energy potential in Germany (Agora Energiewende et al. 2020, blogpost), evaluating cross-border effects in the North sea (Elia et al 2024), or the onshore wind resource potential of Germany (Kleidon 2023, blogpost).

What these applications show is that one can gain relevant insights on wind resource potentials and potential consequences based on physical concepts that are transparent and easily reproducible.

Why higher wind speeds at night are depleted faster

What else is there to find out? The motivation for our new paper was to look at situations where our approach does not work so well, to understand why this is so, and identify possible ways to improve the approach. For this, we used a set of previous numerical model simulations we performed for the state of Kansas in the central US with different intensities of wind turbines in the region (Miller et al. 2015). These simulations showed a curious effect: Wind speeds at night were on average higher than during the day, but when more wind turbines were deployed, nighttime winds were depleted faster than during the day (see Figure below).

This effect can be explained by the mechanism by which winds near the surface are being renewed. Large-scale wind fields are generated mostly within the free atmosphere, that is, high above the surface in more than two kilometers height and more. The winds are brought down to the surface where friction converts the kinetic energy back into heat.

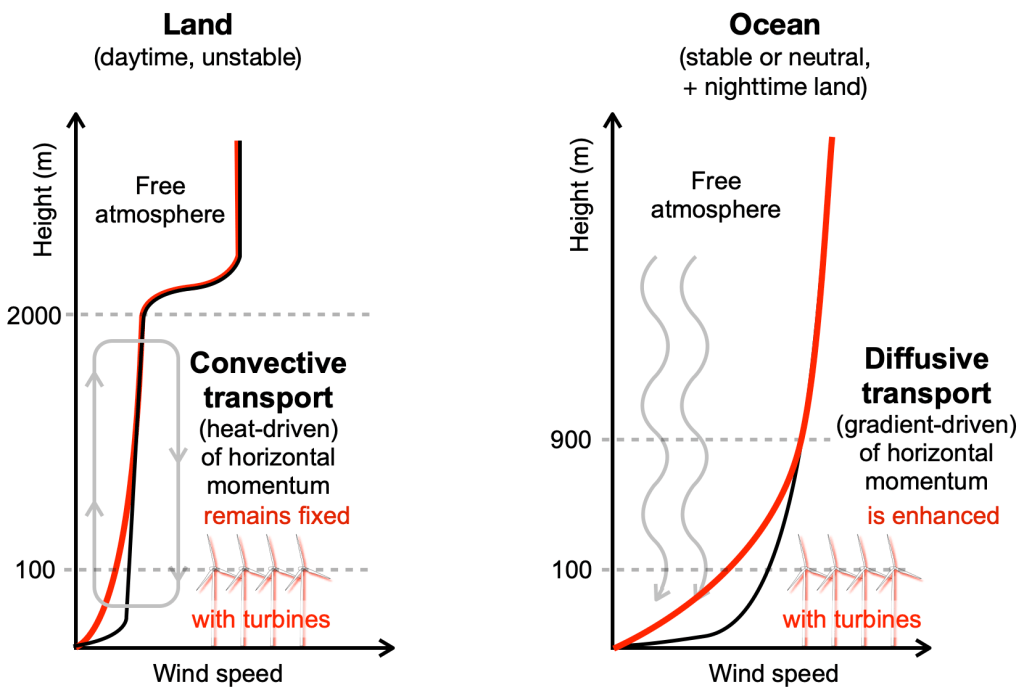

There are essentially two different ways that accomplish this downward transport (illustrated in the Figure below):

(i) During the nighttime, winds are brought down by vertical differences in wind speed. These differences in wind result in shear forces that transport momentum downward to the surface; and

(ii) During the day, sunlight heats the surface, the heated air rises and mixes the lower atmosphere, resulting in a convective boundary layer. The convective, vertical motion reaches higher into the atmosphere and actively brings down the momentum of the winds from aloft.

This difference in how winds near the surface are replenished can explain the behavior of contrasting depletion effects in the model. During the daytime, the reservoir of kinetic energy that the wind turbines see is larger and better mixed, and hence the depletion effect is weakened. During the night, however, the replenishment of winds is slower, resulting in a stronger depletion effect. In meteorology, the different situations are related to stability – at night, the atmosphere is typically stable, that is, void of convective mixing generated by a heating source, while the strong heating during daytime results in unstable situations.

In our KEBA approach, we accounted for this difference in conditions by using different heights of the boundary layer. At nighttime, we used a lower height of around 900 meters, while during the day, we used about 2000 meters. This variation in the height of the KEBA box worked reasonably well, improving the estimates for wind generation and wind speed reductions for daytime and nighttime conditions.

Depletion effects substantially lower the resource potential, but nevertheless yield a lot of power

To illustrate the relevance of the depletion effect, we revisited previously published estimates of the wind resource potential of Kansas. Because our numerical simulations only covered a 4 month summer period, we first used a much longer time series from the ERA-5 reanalysis dataset (a dataset derived from numerical weather forecasts combined with observations). With this extended time series of wind speeds, we then derived a climatological estimate of the wind resource potential for different intensities of installed wind turbines.

Specifically, we evaluated the two scenarios of Lopez et al (2012) and Brown et al (2016). They made slightly different assumptions regarding capacity factors, the density at which wind turbines are being installed, and the area used. In both cases, however, KEBA estimated reductions in capacity factors and generated electricity of more than 60% due to the depletion of the wind resource. These are significant reductions. On the other hand, it still yielded a lot of electricity, more than what Germany currently consumes.

So this application yields a differentiated picture – on the one hand, these depletion effects need to be accounted for. When more wind turbines reduce capacity factors, the levelized cost of electricity goes up, affecting economic considerations. On the other hand, there is still a lot of electricity to be made from wind power.

What‘s next?

Currently, we have a similar study submitted where we evaluate such effects for the setting of offshore wind energy (related to our work with Agora Energiewende) and look at the effects of realistic scenarios for onshore wind energy within Germany. We hope that more of such evaluations will strengthen the use of such simple, yet physically-based tools that allow for more realistic wind resource potentials that can be used in energy policy and scenario modelling.

Reference to Publication

Minz, J. and Kleidon, A. and Mbungu, N. T. (2024) “Estimating the technical wind energy potential of Kansas that incorporates the effect of regional wind resource depletion by wind turbines“, Wind Energy Science 9: 2147-2169. doi:10.5194/wes-9-2147-2024.