Sustainability is a popular topic these days, but what does it actually mean? What does it take to sustain life on Earth in the presence of increased human pressures, and what does it imply for a sustainable future? In a recent paper I combined thermodynamics with an Earth system approach to look at these questions.

The reason for using thermodynamics is simple: living organisms, including humans, depend on energy to sustain their metabolisms. This energy comes in form of carbohydrates contained in the food they consume. Societies need it to sustain their economic activities. This energy does not come for free, but needs to be generated, ultimately out of sunlight. And here, thermodynamics sets the rules for energy conversions, and it sets hard limits for how much energy can at best be generated.

The Earth system approach enters here because it describes the relevant connections and interactions associated with how this energy is consumed or converted further once sunlight becomes useful energy. This shapes the climate in which photosynthesizers generate the energy that sustains life on Earth. Climate, in combination with the rules of thermodynamics, sets the limits to how much energy ecosystems can actually generate. We then need to trace how this energy is consumed and what the consequences are for the system. For a full accounting of these consequences, we need to look at the whole system.

These are our key ingredients. Sustainability from this perspective means to sustain the conditions in which photosynthesizers generate this energy for life, and to allow for this energy to be consumed by the organisms of the natural biosphere – that is, lifeforms excluding humans, their creations, and their livestock. This rather big-picture perspective on sustainability focuses solely on the natural biosphere and how it is impacted by what humans do to achieve sustainable societies and economies. But even if human societies were to stop growing and become sustainable, this inevitably comes at the cost of a degraded natural biosphere. This can only be avoided and reversed if we figure out how we can push the limits that constrain the natural biosphere, so that more energy is generated for all. That’s the main conclusion, and here are the more detailed steps that lead to it.

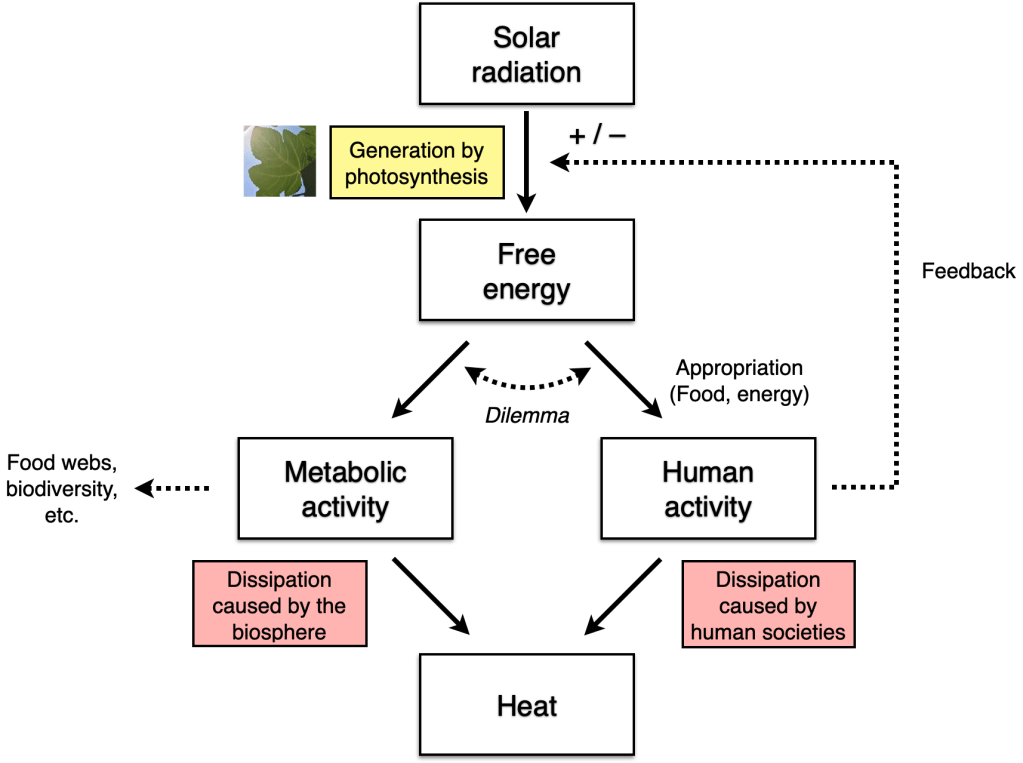

The basic dilemma: Does photosynthesis feed natural consumers or humans?

The energy for life and humans comes from photosynthesis. It uses sunlight, carbon dioxide and water to produce carbohydrates and oxygen. In doing so, photosynthesis does not just convert mass. Most importantly, it generates useful energy, energy that is able to perform work (also called free energy or exergy).

From a perspective of thermodynamics, photosynthesis generates thermodynamic disequilibrium by producing carbohydrates and oxygen out of carbon dioxide and water. Carbohydrates and oxygen represent disequilibrium, because they can be combusted, thus turning them back into the raw materials of carbon dioxide and water, and releasing heat when doing so. Living organisms do exactly this – they use carbohydrates and oxygen to maintain their metabolisms, to grow and build biomass (like plants), or to feed on it (like animals). In doing so, they combust these compounds in a highly controlled way and dissipate this disequilibrium back into its raw materials as well as heat.

From an Earth system perspective, this constitutes an energy conversion chain in which the energy of sunlight (in form of electromagnetic waves) is converted by photosynthesis into chemical energy (in form of carbohydrates and oxygen), which is then converted further by organisms into biomass and heat. The heat is eventually radiated from Earth back into space. This conversion chain follows the second law of thermodynamics at every step.

Humans enter this picture because they also need energy to maintain metabolisms and activities, and to maintain their livestock. They draw this energy from photosynthesis (or from fossil fuels for socioeconomic activities, but we leave this part out here). This human appropriation of energy from the biosphere comes at the expense of the natural consumers, because it reduces the energy that is left for the natural biosphere.

This forms a basic dilemma (Figure 1). Consumers of the energy generated by photosynthesis play a zero-sum game. Any consumption of photosynthetic products by humans comes at the expense of the natural consumers of the biosphere. In other words, the more humans consume, the less available to natural consumers. Even if we reach a somewhat steady level of consumption in which we do not increase our appropriation from the biosphere further, we nevertheless deal with a degraded biosphere.

Figure 1: The dilemma: Humans and natural consumers compete for the energy that photosynthesis produces. The more humans consume, the less is left to sustain the natural biosphere. Figure 1 of Kleidon (2023).

One assumption hidden in this argument is that photosynthesis operates at its limit, so that it cannot generate more energy. Is this actually so? Does carbon uptake by ecosystems operate at its thermodynamic limit? If nature does indeed operate at its limit, then, perhaps, this is like a natural law: systems evolve until they operate at their thermodynamic limit. This assumption actually works rather well when we deal with purely physical processes of the climate system, and we will see in a moment that it works for the biosphere as well. This has a profound implication when applied to human systems: why would we expect that human systems would not evolve to their limit as well? Or, temporarily, even beyond, by depleting energy and resource stocks? If this is a natural law, then we need to identify the means to push the limits of the biosphere, so that human societies can grow without depleting the natural biosphere further.

Photosynthesis works at its limit, and life pushes this limit further

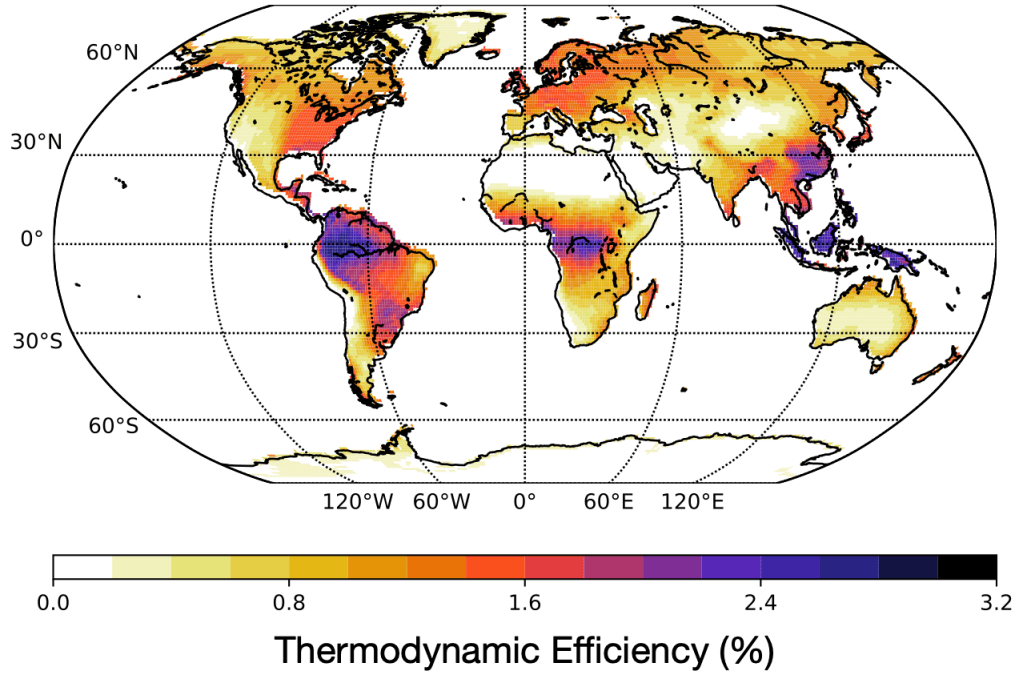

It actually seems that photosynthesis in natural ecosystems indeed operates near its thermodynamic limit in generating energy from sunlight, but it is not as straightforward as it may seem (see also this blogpost). Typically, thermodynamics is applied to the direct conversion of sunlight into carbohydrates. And from that angle it looks like photosynthesis does a lousy job – instead of reaching 18% efficiency, it merely reaches 2-3%.

But carbon fixation needs more than just light. It also needs to take up carbon dioxide from the air to incorporate the solar energy and produce carbohydrates. This uptake is tightly linked to water loss in a relatively fixed ratio referred to as water use efficiency. For each liter of water lost, plants take up the equivalent of about 2 grams of carbon. The water loss by evaporation from the surface is, in turn, thermodynamically limited. Sunlight heats the surface, generates buoyancy and vertical updrafts. This updraft brings the evaporated water from the surface into the atmosphere, replacing it with air from above. Taken together, this exchanges water and carbon between vegetation canopies and the overlying atmosphere.

This exchange of materials with the atmosphere is a thermodynamic process, bringing heat from the warmer surface to the colder atmosphere. The more the air convects, the colder the surface becomes. This leads to a maximum in the power that the atmosphere can generate to fuel atmospheric convection and maintain the gas exchange at the surface. This maximum power limit predicts evaporation very well, for instance over tropical rainforest in Amazonia.

What this implies is that the carbon uptake and energy generation by photosynthesis indeed operates at its limit. This limit does not concern the direct conversion of sunlight into energy, but rather an indirect limitation to generate the necessary transport to supply photosynthesis with carbon dioxide from the overlying atmosphere.

So does vegetation then just passively respond to its physical environment? Not quite. It can optimize its operation, for instance, by stomatal functioning, maximizing the carbon uptake for a certain water loss. And it can push the limit to how much exchange with the atmosphere it can do.

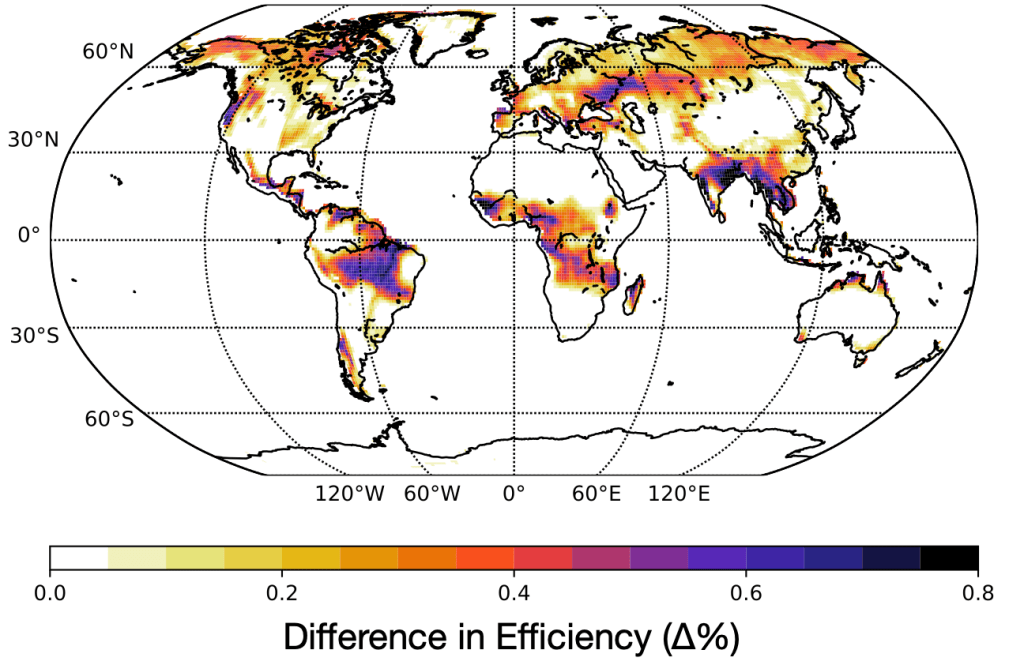

One way by which vegetation pushes the limits is through root systems. Root systems reach deep into the soil, accessing soil water resources that would be unavailable for evaporation of a bare surface. In doing so, vegetated surfaces can recycle more soil water back into the atmosphere than a bare surface. And when vegetation evaporates, it can take up carbon dioxide and be productive. Root systems thus push the limits that the physical environment sets in terms of water supply and demand to a higher level. At the global scale, root systems thereby enhance the productivity by roughly 12%, taking place particularly in the seasonal tropics. (see Figure 2). What this implies is that physical limits are not fixed – they can be pushed to higher levels. And it would seem that this is what vegetation does: pushing the limits. In the grand picture of the planet, this is probably what the whole biosphere did over the course of Earth’s history, having drastically changed the planetary geochemistry to become more productive.

The sustainable solution? Expand the biosphere and generate more!

Let us now get back to humans and sustainability, focusing on the energy they need for their metabolisms and livestocks. This energy is produced by agriculture. Or, phrased differently, humans appropriate the products of photosynthesis, a long-established concept.

And this is a lot. If we start with the energy generated by terrestrial photosynthesis, roughly estimated from the limit described above, this can fix about 224 Terawatt of energy (this is somewhat higher than the 152 TW from observations, because it is only a rough estimate). Half of this is used by plants themselves, so 112 TW remain in form of biomass. When the geographic distribution of this energy generation is combined with a land use dataset, then 31 TW of these take place on pastures and croplands. Not all of this is, of course, directly used by humans, because some of it remains on the fields and some of it feeds livestock. Nevertheless, humans take a considerable share of the energy generated by photosynthesis away from the natural biosphere and dissipate it for their own use.

What can we do to prevent the further depletion of the natural biosphere in the future? If humans continue on their current trajectory, they would increase their appropriation up to their limit, extending their land use into currently naturally vegetated areas. How can we achieve the opposite direction, so that this impact be reduced, given that systems appear to evolve to their limits?

We can also look at this question slightly differently: How can human technology be used to push the limits on generation to higher levels so that more energy is available to all, nature and human societies? Certain forms of technology can achieve this goal. I emphasize “certain” because many technologies would not qualify, because they are simply designed to appropriate more of what photosynthesis provides, but do not push the limits higher. Pesticides, for instance, kill off natural consumers so that humans can appropriate even more of the crop yields. This, and similar forms of technology, are not the means to push the limits higher.

A look back in history is helpful to see which technology can accomplish this goal of pushing limits to photosynthesis to higher levels. A good example is the use of river water for irrigation in the Nile river valley. It diverts water, irrigates plants, which evaporate this water that was not accessible without technology, preventing it from draining into the Mediterranean sea. More evaporation allows for more gas exchange of the vegetative cover. It thus makes the region more productive. Another example are man-made water reservoirs. This form of technology serves a similar purpose as the rooting system of natural vegetation – to balance out periods of water surplus and deficit to enhance evaporation and photosynthesis. Both examples illustrate how limits on photosynthesis can be pushed higher sustainably. Note how different this is from irrigation fed by a non-sustainable overextraction of groundwater. It seems to accomplish the same goal, but typically in a non-sustainable way because the groundwater reservoir is being depleted. There may also be other examples beyond water management of expanding limits, for example regarding nutrient cycling in traditional methods of land management in agriculture.

More generally, we can use technology to extend and move agricultural production into currently unproductive periods and regions, particularly deserts. Then, one would need to take less energy away from naturally productive regions, and thereby leave this energy to be dissipated again by the natural biosphere.

Summing up

When it comes to sustaining life on Earth, we should leave as much of the energy generated by photosynthesis within the natural biosphere for its own consumption – after all, it has the purpose of sustaining the metabolisms of its consumers so that they can fulfill the role they play in ecosystems. The more humans take, the less is left for the consumers, further depleting the biosphere. Even if human consumption reaches a steady state or is reduced, it would still leave the natural biosphere depleted. It seems that the only way to avoid this depletion is to “expand” the biosphere into regions that are currently unproductive. This can be done using certain forms of technology, because these provide means to retain or obtain freshwater that are not available to nature by its own means. This would then allow human societies to behave like natural systems – to grow to their limit, and to find the means to push these further. And this in a way that sustains both, life and humans.

And, at the end, a personal note

We typically write these blogposts when a new paper from our group was published, so that this was long overdue. I finally started writing this post when I received an e-mail from the Center of the Advancement of the Steady State Economy, inviting me to write a post for their blog, and we agreed that it would be posted on both blogs. But then, in the end, they declined. It seemed that my notion of a path of sustainable growth did not fit their ideology. I think this is quite unfortunate, because it does not help us to advance. Ideologies never help us to solve the many pressing problems that we are currently facing on the planet, even when they are well meaning.

Reference

Kleidon, A. (2023). Sustaining the Terrestrial Biosphere in the Anthropocene: A Thermodynamic Earth System Perspective. Ecology, Economy and Society — the INSEE Journal, 6, 53-80. https://doi.org/10.37773/ees.v6i1.915