Entropy has intrigued me for a long time – it usually comes up at the very end of asking “why” questions. It is such a fundamental concept in physics, but then – why does nobody talk about it in Earth system science? My review paper just published in Earth System Dynamics explains why entropy is so essential to understand the dynamics of the Earth system: because it limits how much work can be done, and work is at the very core of what we call dynamics.

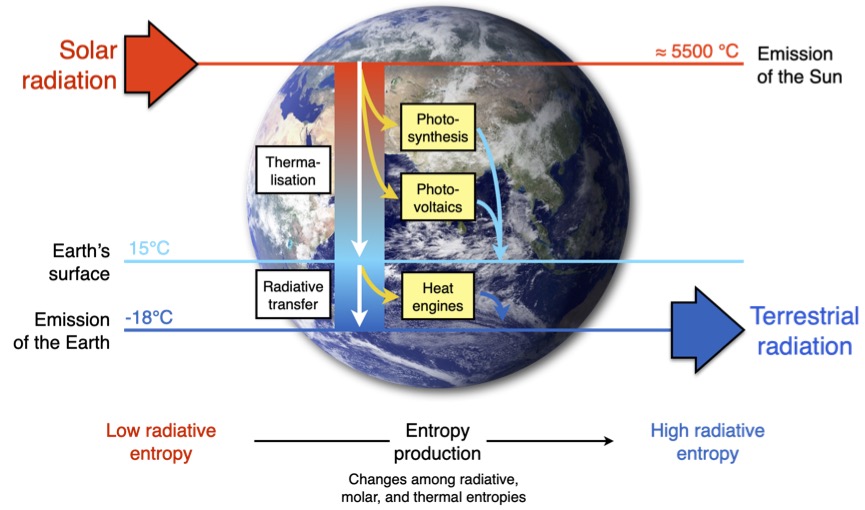

Figure 1 of Kleidon (2023).

The review paper just published is an update to the book I published a few years back, and to big papers I published on entropy even before that time (Kleidon 2004, Kleidon 2009, Kleidon 2010, Kleidon 2012). The motivation for it actually came from my wife Anke, who is also a scientist. Sometimes I am asked about why I no longer work on Maximum Entropy Production (MEP, e.g. Ozawa et al 2003, Kleidon and Lorenz 2005, Martyushev and Seleznev 2006, Kleidon et al. 2010). Anke said, “Axel, you need to clarify this before doing new research”.

To address this question on MEP quickly: I no longer work on MEP because I found something much better – better, because it is much easier to understand, more predictive and more relevant. For me, MEP reflects a past state of my knowledge, it had its place, but at the time, I did not fully understand the significance of entropy and its connection to work. Since then, my knowledge has progressed and has become clearer. With the use of entropy and the equally important aspect of taking a true systems perspective of the whole Earth, we can now predict aspects of Earth system functioning in very simple terms that are based entirely on physics. I am still fascinated by its success. This perspective estimates relevant aspects of Earth system functioning at a level that I had not believed would be possible ten years ago.

In this blogpost I want to summarize the key points that I think are essential to understand the role of entropy in the Earth system and that are not widely acknowledged, as well as why it is so central. The more technical details can be found in the paper.

Entropy is more than classical thermodynamics – it’s quantum physics

Entropy started with Rudolf Clausius in the mid 19th century and is key to what’s called classical thermodynamics, including the famous second law of thermodynamics. But the concept of entropy was developed further, beyond classical thermodynamics. Ludwig Boltzmann gave a mechanistic explanation of entropy by introducing the kinetic theory of gases. In this approach, he interpreted entropy as the probability of how energy is distributed among a finite number of molecules that make up the gas. Entropy lost its mystical appearance and became the probability of distributing a total amount of energy across the molecules of the gas.

Boltzmann’s mechanistic interpretation of entropy is already beyond classical thermodynamics, and it keeps getting better. At the onset of the 20th century, Max Planck picked up Boltzmann’s approach, and used it to derive radiation laws, using essentially the same approach. Instead of energy being distributed over molecules, he distributed it over discrete chunks of radiation, or photons. This led to the notion that energy is quantized, with photons being a reflection of this. With this notion of photons, a discrete number of states over which energy can be distributed over radiation, and the assumption of maximum entropy, he derived the black body spectrum of radiation and the Stefan-Boltzmann radiation law – which was not possible before without considering that energy is quantized. Maximum entropy means that photons are distributed in the most probable way, just like what Boltzmann introduced for describing a gas. This quantized nature of light was confirmed when Albert Einstein used it to explain the photoelectric effect. It was the birth of quantum mechanics and statistical physics, which revolutionized physics at the onset of the 20th century. It separated the world into the microscopic world of photons, electrons, and molecules with quantized amounts of energy and the macroscopic world of classical physical theories, such as thermodynamics, mechanics, fluid dynamics and gravity.

The practical relevance of this is that entropy has a much wider meaning than that in classical thermodynamics. Entropy is needed to translate the dynamics from the microscopic world of quantum physics into the macroscopic world of classical physics. And there is not just one form of entropy around, but at least three different forms relevant to the Earth system (Section 2.1 and Figure 3 in the review paper):

- radiative entropy, with energy being distributed across different photons and wavelengths of radiation;

- molar entropy, with energy being distributed across different states of electrons in atoms and molecules; and

- thermal entropy, with energy being distributed across the different states of wobbling and motion of molecules – the form of entropy that classical thermodynamics focuses on and that Boltzmann introduced.

These different forms of entropy are associated with well-established distributions in statistical physics: the Bose-Einstein statistics for photons, the Fermi-Dirac statistics for electrons, and the Maxwell-Boltzmann statistics for molecules. Even though these different forms of entropy are not well recognized, they are extremely well established in modern physics and have been around for quite some time.

This distinction of the three forms of entropy matters when we deal with energy in the Earth system. When sunlight illuminates the Earth, its energy is in form of radiation, and it has a very low radiative entropy. This low entropy is characteristic of the high emission temperature of the Sun (see Figure 1 above), and is reflected in the high frequencies of sunlight, being centered in the visible range. Energy is not represented as heat, i.e., not by the random motion of molecules, but it is spread over electromagnetic waves. When this energy is absorbed by the Earth system, the energy changes its form, and so does the entropy. In the end, this energy is emitted from Earth back into space, again in form of radiation, but at much longer wavelengths, because it was emitted at the much colder temperatures on Earth. This represents an energy flux of much higher entropy, but, again, not in form of heat, but in form of electromagnetic waves. It is this difference in radiative entropy which allows the Earth to maintain a state of disequilibrium, and it allows Earth system processes to perform work.

So when you think of entropy and the Earth system, think beyond classical thermodynamics – it is about quantum physics.

To work or not to work – that makes a big difference

Entropy is highly relevant because it sets the limit to how much work can be done. And being able to perform work makes a big difference (Section 2.2 and Figure 4 in the review paper).

You can use wood, for instance, and just burn it and heat the environment. Or you can use it to run a steam engine and let it do work. Just burning it dissipates the chemical energy stored in wood into heat, it produces entropy, because it releases this heat at a certain temperature. This is where Clausius’ expression for entropy ∆S = ∆Q/T comes into play.

When using the heat to fuel a steam engine, some of the energy goes into performing work. The dissipation into heat occurs later, when the energy resulting from the work is being dissipated and turns into heat. In a steady state, in which the work done is balanced by the dissipative loss, both systems produce entropy, but only the latter involves work. So entropy production is not really a meaningful way to look at processes. We cannot distinguish a system that performs work from one that does not.

When it comes to the Earth system, work makes all the difference. The Earth is more than an inhabitable piece of flying rock, and this relates to the work done on the planet. Work drives motion and cycling, work creates chemical compounds that run life, and work creates the electricity needed by human societies and economies. So the question then becomes how entropy comes into play to set the limits to make solar radiation perform work.

Entropy sets the limit to work

Entropy sets limits to how much work can be derived from a low-entropy energy source. This is well known. In fact, since Sadi Carnot, who defined the Carnot limit before it was being derived from classical thermodynamics. This limit can be derived directly from the first and second law of thermodynamics, in a very general way (Section 2.3 and Figure 5 in the review paper). It does not need specifics on how it is being done, that is, we do not need to assume a specific thermodynamic cycle. The limit is not restricted to heat either – the same concepts are used to derive the theoretical limits of photosynthesis and solar panels, that is, radiative conversions, conversions that do not deal with heat.

I use work as the starting point to define free energy: when work is done, free energy is generated (Section 2.2 in the review paper). When one does the math, it turns out that this is what is assumed in the derivation of the Carnot limit: that the energy that goes into work has no entropy. So let’s call it free energy, because it is free of entropy. When this energy is dissipated, then it turns back into heat, that is, in a form of energy with entropy, thus producing entropy.

Why is this relevant? Well, the dynamics of Earth system processes – accelerating mass into motion, cycling elements, converting chemicals and so on all need work to be maintained. If the Earth would not perform work, it would be a really boring planet.

So when you think about energy conversions, think of work done and free energy generated. And follow this free energy through its conversions until it is dissipated back into heat. I found this to be a much more informative approach than just looking at entropy production of processes and entropy budgets.

Planetary power plants – they work to maintain the dynamics of the Earth system

How and how much work is done within the Earth system? And who does the work? There are only a very few mechanisms that can do the job (Section 2.6 in the review paper).

First and foremost, there are heat engines (yellow boxes in Figure 1 above), driven by differences in heating and cooling within the Earth system. They involve the basic mechanism by which power plants or combustion engines work. And this is classical thermodynamics. Heat engines need a heat source with a higher temperature and a heat sink with a lower temperature.

For the Earth, such a difference in temperature is typically created by differences of where solar radiation is absorbed and heats the planet, and where emission of terrestrial radiation to space takes place. The primary example for this is the heating of the surface by sunlight, making it warm, while the atmosphere cools by emitting radiation, making it colder. This difference in heating and temperatures represents a difference in entropy fluxes – heating the surface by absorption results in adding heat with lower entropy (think of Clausius’ expression for entropy), cooling the atmosphere by emission removes heat with a higher entropy. From this difference in entropy, work can be done, resulting in free energy.

In practice, there are a few heat engines operating: (i) surface heating results in dry convection, (ii) heating by condensation results in moist convection, (iii) the differential heating between tropics and poles results in the large-scale atmospheric circulation. There are a few others, such as sea breeze systems or mantle convection in the Earth’s interior. Nevertheless, it is these three heat engines that primarily drive the dynamics of the physical Earth system that shape climate.

But that’s not all. This is where we need to go beyond classical thermodynamics. In principle, solar radiation has a very low entropy – after all, solar radiation was emitted at a very hot temperature. So what happens to the low entropy of solar radiation when it reaches the Earth and turns into heat? The solar photons are absorbed by electrons, raising them into elevated, or excited, states. From these, they decay back to their ground state, but they do this through some intermediate states. In doing so, they emit more photons of lesser energy. No work is done. Absorption and subsequent emission just produces a lot of entropy. This process is called thermalization (see box in Figure 1 above) – photons are absorbed and emitted until they reach their equilibrium with the ambient temperature at which the radiation is being absorbed. This entropy production by absorption of solar radiation is by far the biggest contribution to the entropy production of the planet.

This huge waste of low-entropy sunlight can be avoided. The primary process that achieved this is photosynthesis, at least to some extent. It uses the excited photons, prevents their decay, and uses them to perform the work of splitting water and separating the electron from its nucleus. This is the first step of photosynthesis, also called light reactions. So instead of the low-entropy solar photons being thermalized and converted into heat, some of them are used to perform the work of charge separation and generate electric energy. Subsequently, this electric energy is stored in short-lived ATP, which is then converted into longer-lived carbohydrates and oxygen (the dark reactions). Overall, this creates free energy in chemical form. It is associated with the thermodynamic disequilibrium between reduced carbon compounds – such as carbohydrates, biomass and fossil fuels – and atmospheric oxygen. This chemical energy is used to drive the dynamics of the biosphere: it fuels the metabolic activities of plants, animals, and us humans.

Photovoltaics, that is, the human-made technology based on the photoelectric effect, is even better than photosynthesis in avoiding the thermalization loss. In principle, it does something very similar to photosynthesis – it uses solar photons to perform the work of charge separation, generating electric energy and thereby avoiding thermalization. But photovoltaics does not need to take up carbon dioxide from the air to store its energy – it simply feeds the energy into the electricity grid. Photosynthesis depends on the heat engines of the Earth system to deliver the carbon dioxide, which sets its bottleneck. Because photovoltaics does not depend on this gas exchange, it is considerably more efficient in generating free energy than photosynthesis.

So we have three processes that perform work out of sunlight (yellow boxes in Figure 1 above):

(i) Heat engines, using differences in solar heating and radiative cooling. They run physical climate processes, but have a low efficiency because they cannot avoid the thermalization of solar photons so they can only utilize relatively small temperature differences;

(ii) Photosynthesis, using solar photons to perform the work of charge separation. By avoiding thermalization, photosynthesis could be quite efficient – except that it needs carbon dioxide, and its supply is hampered by the low efficiency of the heat engines that maintain transport in the Earth system and deliver it to the photosynthesizers. It results in a very low efficiency of photosynthesis;

(iii) Photovoltaics, which also uses solar photons to separate charges. It is a human-made technology that is highly efficient in avoiding thermalization, although it has not quite yet achieved the status of being a planetary energy-generating process at the same level as photosynthesis and heat engines.

Working at the limit – this makes Earth system functioning highly predictable

So far, so good – Earth system processes perform work. This insight on its own does not lead to a predictive constraint. What does is the assumption that processes work at their limit, that is, they work as hard as they can. Then, no matter how complex the process is, one can infer its magnitude of the process as well as its consequences from the limit. It implies that the performing work is the primary constraint on the dynamics.

And indeed, this seems to be the case. Although, to describe limits within the Earth system, we need to look at the whole – not just how work is being performed, but also at its consequences. That’s more than looking at a power plant in isolation, we need to look what the generated work does and how it alters the Earth system. When heat engines operate in the atmosphere, they generate motion. Motion transports heat, and this heat transport depletes the temperature difference that drives the heat engine in the first place. That effect reduces the efficiency of the engine.

This leads to another limit: the maximum power limit (Section 2.4 and Figure 6 in the review paper). In this limit, the Carnot limit from the laws of thermodynamics is combined with the energy balances of the Earth system that describe the temperature difference of the efficiency term and that is being depleted by the resulting heat transport. With more power, we get more motion, more heat transport and more power, but it results in a lower temperature difference, lower efficiency, which reduces the power. This results in the maximum power limit, with an optimum heat flux and optimum temperature difference associated with the maximum.

When using the maximum power limit with the observed radiative forcing of the Earth system, one can predict heat fluxes, energy balance partitioning, and temperatures very well. The atmosphere appears to work at its limit, it appears to work as hard as it can. So the maximum power limit, the combination of the Carnot limit and the interactions with the energy balances, adds another relevant constraint to the dynamics of the Earth system.

Despite the overwhelming complexity of the Earth system – the atmosphere aims to maximize its power, and that makes it highly predictable from relatively simple physical constraints on how work is derived from the solar radiative forcing.

The whole Earth is more than the sum of its parts – connections and interactions are critical

The maximum power limit illustrates nicely how important an Earth system perspective is – that is, to not just look at the detailed process, but to look at the whole. Why? Because the maximum power limit is not just about thermodynamics. It combines the interaction of the resulting dynamics with the driving temperature difference. This temperature difference is thus not fixed, as it is typically assumed in classical thermodynamics. The results of the heat engine interact with the boundary conditions that drive it. It illustrates the importance of interactions for Earth system functioning at a profound level. At the same time, this interaction is very well constrained by the energy balances, as it is done in the derivation of the maximum power limit.

This application of maximum power works quite well – it can predict surface energy balance partitioning, and large-scale heat transport very well. It seems to suggest that thermodynamics and maximum power is something quite general, and we can apply it to other Earth system processes as well.

But it is not as simple as that. This manifestation of maximum power is quite a special case, because it deals with the conversion of heat into the work to maintain motion. And since solar radiation is the dominant cause for heating, it is at the top of the energy conversion chain on Earth. Other processes do not have this direct interaction with heat redistribution and the radiative forcing of the planet, so the maximum power limit is not that widely applicable.

There are, nevertheless, other processes that indirectly reflect the maximum power limit, because those processes depend heavily on motion, transport and mixing. The examples I use in the paper are evaporation and photosynthesis on land (Section 3.2 and 3.3 in the review paper). Both processes are intimately linked with the gas exchange between the surface and the atmosphere: the evaporated water at the surface needs to be transported into the atmosphere, and plants need to get their carbon dioxide from the air. This gas exchange is maintained by mixing. This mixing is, in turn, strongly shaped by the presence of buoyancy or frictional dissipation, with its magnitude set by the maximum power limit. The consequences of the maximum power limit can then predict evaporation rates and photosynthetic carbon uptake by terrestrial vegetation very well as well. This represents an indirect manifestation of the maximum power limit. It does not deal with a trade-off between flux and driving difference that generates the power to drive the process, but it is rather that their exchange rides on the buoyant transport generated by surface heating.

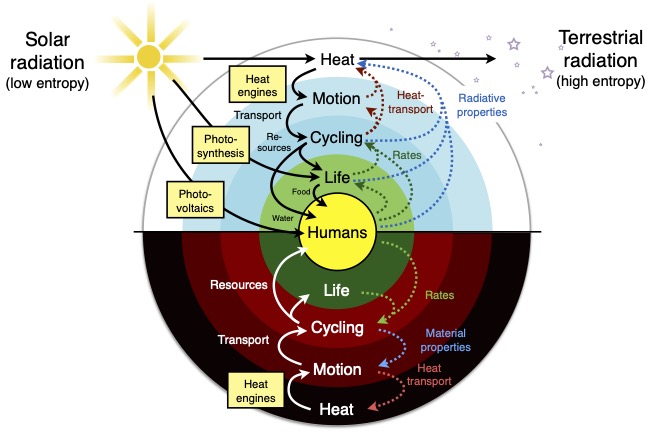

What this means is that we need a hierarchical view of the Earth system, as shown in Figure 2. There is the planetary driver of solar radiation, which is converted into heat once absorbed – the outermost shell of the diagram. From this heating, heat engines work to generate motion – so a fraction of the heat is converted into kinetic energy, the next shell in the figure. This motion maintains cycling – as demonstrated by the success to derive evaporation rates from the maximum power limit, shaping another shell. As carbon uptake by vegetation is closely linked to evaporation, this connects and constrains the dynamics of the next shell. This sequence of connections is shown by the arrows on the left side between the different shells shown in Figure 2.

The resulting dynamics leave their effects. They alter reaction rates and resulting concentations, heat redistribution, and the radiative forcing, that is, the environment in which all energy conversion processes take place. These effects thus feed back to the planetary drivers, altering the conditions to perform the work on the planet.

More maximum power – indirect limits and ways to push these

In addition to the indirect manifestation of the maximum power limit of generating motion, there are also other limits that maximize power, although they are not thermodynamic.

One example from our own research is about how much wind energy can at best be used as renewable energy. The topic sounds quite far removed from the previous, more general descriptions. But, in the end, what wind turbines do is that they use the kinetic energy of the winds, and instead of them being dissipated by friction and converted back into heat, turbines convert the energy into electricity – another form of free energy that can perform further work. This example thus falls in the general scheme of “following the energy” after it has been generated by Earth’s heat engines.

Here, too, a maximum in how much wind turbines can use can be identified (Miller et al. 2011): The more wind turbines there are, the more they remove momentum, slowing down wind speeds. Since the extracted power is the product of momentum and velocity, there is a maximum that can easily be calculated. This limit reproduces the behavior of much more complex weather simulation models very well (Miller et al. 2015, Miller and Kleidon 2016, Kleidon 2021) and can be used to estimate such effects in renewable energy scenarios (Kleidon 2023b). Present-day wind energy use is, however, much, much less than what this limit implies.

To bring this back to a more general level: Once sunlight has been put to work and generated free energy, this energy can be converted further into other forms of free energy. And to those conversions, the maximum power limit may also provide useful insights.

I also want to give one example of how limits can also be pushed, dealing with the beneficial effects that root systems of vegetation have on the biosphere. Again, this example seems not quite so close to the general explanations of energy conversions and limits described above. The connection is that the limit to vegetation activity is set by gas exchange and evaporation, both indirect reflections of the maximum power limit, but this limit on vegetation productivity can be pushed to higher levels (Kleidon 2023a).

Here is how this works: Precipitation in some regions comes only in certain periods, with other times being dry. Storing rainwater and using it later can thus enhance evaporation during dry episodes. This is what vegetation does. Root systems allow vegetation to reach deeper soil layers and extract the water there – water that by abiotic means is unavailable to support evaporation at the surface. So in this sense, vegetation provides a “plumbing” system, making water available for evaporation during dry episodes. It thus enhances evaporation when otherwise it would be limited by water availability.

The benefit for vegetation is rather direct: greater water availability means longer periods of gas exchange, allowing for greater productivity. So the limit of gas exchange can be pushed by storing water, extending gas exchange into dry episodes.

These examples show that there is more to explore regarding maximum power limits in the Earth system. The first example regarding wind energy use shows that there may be maximum power limits to further energy conversions once sunlight has been put to work. The second example shows that some effects or feedbacks can push limits further. Yet, both examples also show that it requires more specific settings to provide meaningful insights. It does not require much detail, just a bit. And the results still turn out to be rather simple and insightful.

MEP is not helpful to identify mechanisms and to predict magnitudes

To come back to the onset of this blogpost and the proposed MEP hypothesis that systems maximize entropy production: Can all this be predicted equally by maximizing entropy production?

The view described here and MEP certainly have something in common. In a steady state, maximum power in motion also means a maximum rate of dissipation. As this converts free, kinetic energy back into heat, it produces thermal entropy. If power is maximized, so is dissipation. Then, the thermal entropy production is maximized as well. So one could argue that this is the same thing, but MEP is more general, and that this should be the “real” principle.

But this interpretation is flawed. As described above, it makes a big difference if processes perform work, or if they do not. Think about the process of thermalization described above. By just looking at entropy production, we cannot tell the difference between solar radiation being thermalized when it turns into heat, wasting its low radiative entropy, or whether it is absorbed by a canopy and used to perform work, and only later being dissipated into heat. In steady state, we cannot distinguish one case from the other. It requires this critical distinction between work and waste.

It also requires the connections among processes, particularly with motion: hydrologic cycling as well as carbon exchange of terrestrial vegetation appear limited by the extent of mixing. As mixing is limited by the maximum power limit, this can predict their observed, simple patterns. But this is an indirect manifestation of the maximum power limit. A direct application of maximum entropy production to the process, without the system’s perspective that embraces the whole, one would not be able to explain, for instance, the very low efficiency of observed photosynthetic rates.

So overall, I think MEP was useful as a working hypothesis for the time being – it certainly stimulated a lot of research. For me, it is time to move on, get real and use something better that is closer to the physics and mechanisms at work. Look at which process does the work and what happens to the results of this work. Follow the free energy, to see how the bottlenecks set by the work done trickle down energy conversion sequences. To me, that’s a much more powerful perspective of Earth system dynamics than an evaluation in terms of their entropy production, because it is predictive.

“Working at the limits” yield simple, profound, and relevant insights

So what can we learn from this approach that we cannot if we don’t consider entropy?

At the more theoretical side, this approach yields hard limits on how much work can be done by Earth system processes – the power plants that were described above. These limits come from the requirement of the second law and add a further, relevant constraint to the dynamics in terms of how much work is done. Since the estimates derived from the limits – directly or indirectly – reproduce observations very well, it provides a simple, yet profound way to do Earth system science: Natural Earth system processes appear to work at their limit, thus making them predictable.

There are a range of applications for this approach with practical implications.

The limits of the physical heat engines working at maximum power yield optimum heat fluxes and temperature differences – that is, key variables of climate. So we can use this approach to do research on climate and global climate change. Typically, this is done numerically, using big simulation models on huge computers. This is because dynamics play an important role in shaping energy balances, so that these physical concepts alone cannot be used to make estimates. The maximum power limit yields another constraint, one on the dynamics – and then, with this additional constraint, we can do simple and transparent estimates again using energy balances. We have already done some applications showing the strength of this approach, i.e., to explain climatological temperature variations across land (Ghausi et al. 2023) or the difference in climate sensitivity over ocean and land (Kleidon and Renner 2017). The missing constraint on the dynamics comes from entropy – after all, it is the second law that sets the Carnot limit of the heat engine and thus how much work can be done to generate dynamics.

While “work” and “limits” may sound somewhat abstract, these terms become much more concrete and highly relevant when we think of them in the context of renewable energy (Kleidon et al. 2016). After all, Earth system processes need to perform work so that the resulting free energy can be used as renewable energy. The approach yields an Earth system’s perspective on the limits and interdependencies of different forms of renewable energy. It provides an explanation for the very low efficiency by which the atmosphere generates kinetic energy, and it connects the energy of winds with subsequent conversions to the power of ocean waves and currents. One can then immediately see that the direct use of solar radiation by photovoltaics has a tremendously higher resource potential than any form that was generated by one of Earth’s heat engines, or even by photosynthesis. It is only photovoltaics that avoids thermalization of solar photons and does not depend on Earth’s heat engines, like photosynthesis, which is why it has by far the greatest resource potential for renewable energy. Since photovoltaics avoids the huge loss and entropy production when sunlight is absorbed, this comes back down to entropy.

We have also applied this approach to broader questions. In Frank et al (2017), for instance, we used it to distinguish planets according to which kind of work they do: none – like Mercury, heat engines – like Venus, Earth and Mars, photosynthesis – like life on Earth, and photovoltaics – like civilizations on hypothetical planets. In Kleidon (2022) I applied it to the Gaia hypothesis, where planetary regulation by life was associated with the possibility that the biogeochemical changes introduced by life may alter the radiative forcing to make heat engines even stronger, and life on the planet, literally, more powerful. Last, but not least, I applied it in Kleidon (2023) to the question of sustainability. When humans use energy from the planet – either the energy created by photosynthesis for food or the free energy of the climate system to meet primary energy needs – then they weaken the dynamics of the natural system. That’s not sustainable in the long run. What is needed is that human societies allow the Earth to perform more work, which can only be done by avoiding thermalization in the use of sunlight – as in photovoltaics.

These examples build on this approach – that work is done in the Earth system, shaping climate, that life and humans alter the conditions and uses of this work. This work, again, in the end being constrained by entropy and the second law, although in the broader sense of modern physics rather than classical thermodynamics.

What’s next?

For me, the most important next steps are to use these basics to teach and educate, along with more applications (and there is more cool stuff on the way). There are currently such grave challenges for human societies, be it global warming or the biodiversity crisis. To face these, we need to be well informed and make the best decisions – rational, and based on science.

Such a well-informed basis needs to have a real understanding of the problem, not in form of believing huge black-box simulation models, but in form of understanding the basics in terms of the simplest formulations possible, reducing the problem to the essential physics. These formulations – obviously – will not allow for the best prediction, that’s not their aim. They show if we really understand the core of the problem. And entropy, limits to work, and the Earth system context set the essential physics for such simplest formulations.

References

Kleidon (2004) Beyond Gaia: Thermodynamics of Life and Earth System Functioning. Climatic Change 66: 271-319.

Kleidon (2010) Life, hierarchy, and the thermodynamic machinery of planet Earth. Physics of Life Reviews 7: 424-460.

Kleidon (2012) How does the Earth system generate and maintain thermodynamic disequilibrium and what does it imply for the future of the planet? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London – Series A 370,1012-1040.

Kleidon (2016) Thermodynamic foundations of the Earth system. Cambridge University Press.

Kleidon (2023) Working at the limit: A review of thermodynamics and optimality of the Earth system. Earth System Dynamics 14: 861-896.